Designing a Pure Python Web Framework

A look at how Reflex works under the hood.

Nikhil Rao

·

We started Reflex a year ago so that anyone who knows Python can easily build web apps and share them with the world, without needing to learn a new language and piecing together a bunch of different tools.

In this post, I'll share more about what makes Reflex different, and how it works under the hood.

We'll use the following basic app that displays Github profile images as an example to explain the different parts of the architecture.

Web development is one of the most popular use cases for programming. Python is one of the most popular programming languages in the world. So why can't we build web apps in Python?

Before working on Reflex, I worked on AI projects at a startup and then at a big tech company. On these teams, we used Python for everything from data analysis to machine learning to backend services. But when it came to building user interfaces or apps so that others could use our work, there wasn't a good option to stay in Python. Suddenly, we had to switch to JavaScript and learn a whole new ecosystem.

Making a UI should be simple, but even though we had great engineers on our team, the overhead of learning a new language and tools was a huge barrier. Often making a UI was harder than the actual work we were doing!

There were a few ways already to build apps in Python, but none of them fit our needs.

On the one hand, there are frameworks like Django and Flask that are great for building production-grade web apps. But they only handle the backend - you still need to use JavaScript and a frontend framework, as well as writing a lot of boilerplate code to connect the frontend and backend.

On the other hand, pure Python libraries like Dash and Streamlit can be great for small projects, but they are limited to a specific use case and don't have the features and performance to build a full web app. As your app grows in features and complexity, you may find yourself hitting the limits of the framework, at which point you either have to limit your idea to fit the framework, or scrap your project and rebuild it using a "real web framework".

We wanted to bridge this gap by creating a framework that is easy and intuitive to get started with, while remaining flexible and powerful to support any app.

- Pure Python: Use one language for everything.

- Easy to get started: Build your ideas easily without needing web development experience.

- Full flexibility: Web apps should match the customizability and performance of traditional web frameworks.

- Batteries included: Handle the full-stack from the frontend, to the backend, to deployment.

Now let's dive into how we built Reflex to meet these goals.

Full-stack web apps are made up of a frontend and a backend. The frontend is the user interface, and is served as a web page that runs on the user's browser. The backend handles the logic and state management (such as databases and APIs), and is run on a server.

In traditional web development, these are usually two separate apps, and are often written in different frameworks or languages. For example, you may combine a Flask backend with a React frontend. With this approach, you have to maintain two separate apps and end up writing a lot of boilerplate code to connect the frontend and backend.

We wanted to simplify this process in Reflex by defining both the frontend and backend in a single codebase, while using Python for everything. Developers should only worry about their app's logic and not about the low-level implementation details.

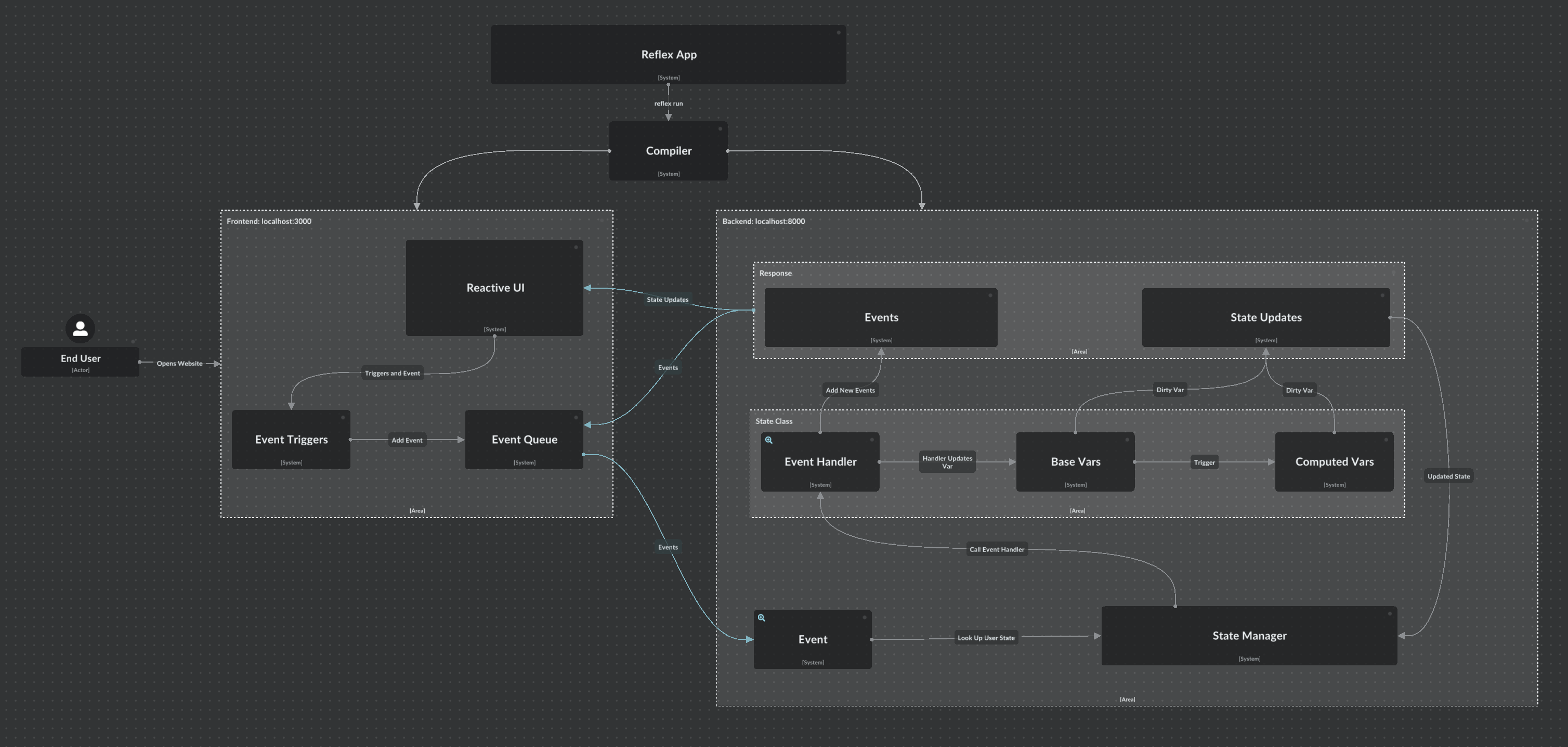

Under the hood, Reflex apps compile down to a React frontend app and a FastAPI backend app. Only the UI is compiled to Javascript; all the app logic and state management stays in Python and is run on the server. Reflex uses WebSockets to send events from the frontend to the backend, and to send state updates from the backend to the frontend.

The diagram below provides a detailed overview of how a Reflex app works. We'll go through each part in more detail in the following sections.

We wanted Reflex apps to look and feel like a traditional web app to the end user, while still being easy to build and maintain for the developer. To do this, we built on top of mature and popular web technologies.

When you reflex run your app, Reflex compiles the frontend down to a single-page Next.js app and serves it on a port (by default 3000) that you can access in your browser.

The frontend's job is to reflect the app's state, and send events to the backend when the user interacts with the UI. No actual logic is run on the frontend.

Reflex frontends are built using components that can be composed together to create complex UIs. Instead of using a templating language that mixes HTML and Python, we just use Python functions to define the UI.

In our example app, we have components such as rx.hstack, rx.avatar, and rx.input. These components can have different props that affect their appearance and functionality - for example the rx.input component has a placeholder prop to display the default text.

We can make our components respond to user interactions with events such as on_blur, which we will discuss more below.

Under the hood, these components compile down to React components. For example, the above code compiles down to the following React code:

Many of our core components are based on Radix, a popular React component library. We also have many other components for graphing, datatables, and more.

We chose React because it is a popular library with a huge ecosystem. Our goal isn't to recreate the web ecosystem, but to make it accessible to Python developers.

This also lets our users bring their own components if we don't have a component they need. Users can wrap their own React components and then publish them for others to use. Over time we will build out our third party component ecosystem so that users can easily find and use components that others have built.

We wanted to make sure Reflex apps look good out of the box, while still giving developers full control over the appearance of their app.

We have a core theming system that lets you set high level styling options such as dark mode and accent color throughout your app to give it a unified look and feel.

Beyond this, Reflex components can be styled using the full power of CSS. We leverage the Emotion library to allow "CSS-in-Python" styling, so you can pass any CSS prop as a keyword argument to a component. This includes responsive props by passing a list of values.

Now let's look at how we added interactivity to our apps.

In Reflex only the frontend compiles to Javascript and runs on the user's browser, while all the state and logic stays in Python and is run on the server. When you reflex run, we start a FastAPI server (by default on port 8000) that the frontend connects to through a websocket.

All the state and logic are defined within a State class.

The state is made up of vars and event handlers.

Vars are any values in your app that can change over time. They are defined as class attributes on your State class, and may be any Python type that can be serialized to JSON. In our example, url and profile_image are vars.

Event handlers are methods in your State class that are called when the user interacts with the UI. They are the only way that we can modify the vars in Reflex, and can be called in response to user actions, such as clicking a button or typing in a text box. In our example, set_profile is an event handler that updates the url and profile_image vars.

Since event handlers are run on the backend, you can use any Python library within them. In our example, we use the requests library to make an API call to Github to get the user's profile image.

Now we get into the interesting part - how we handle events and state updates.

Normally when writing web apps, you have to write a lot of boilerplate code to connect the frontend and backend. With Reflex, you don't have to worry about that - we handle the communication between the frontend and backend for you. Developers just have to write their event handler logic, and when the vars are updated the UI is automatically updated.

You can refer to the diagram above for a visual representation of the process. Let's walk through it with our Github profile image example.

The user can interact with the UI in many ways, such as clicking a button, typing in a text box, or hovering over an element. In Reflex, we call these event triggers.

In our example we bind the on_blur event trigger to the set_profile event handler. This means that when the user types in the input field and then clicks away, the set_profile event handler is called.

On the frontend, we maintain an event queue of all pending events. An event consists of three major pieces of data:

- client token: Each client (browser tab) has a unique token to identify it. This let's the backend know which state to update.

- event handler: The event handler to run on the state.

- arguments: The arguments to pass to the event handler.

Let's assume I type my username "picklelo" into the input. In this example, our event would look something like this:

On the frontend, we maintain an event queue of all pending events.

When an event is triggered, it is added to the queue. We have a processing flag to make sure only one event is processed at a time. This ensures that the state is always consistent and there aren't any race conditions with two event handlers modifying the state at the same time.

There are exceptions to this, such as background events which allow you to run events in the background without blocking the UI.

Once the event is ready to be processed, it is sent to the backend through a WebSocket connection.

Once the event is received, it is processed on the backend.

Reflex uses a state manager which maintains a mapping between client tokens and their state. By default, the state manager is just an in-memory dictionary, but it can be extended to use a database or cache. In production we use Redis as our state manager.

Once we have the user's state, the next step is to run the event handler with the arguments.

In our example, the set_profile event handler is run on the user's state. This makes an API call to Github to get the user's profile image, and then updates the state's url and profile_image vars.

Every time an event handler returns (or yields), we save the state in the state manager and send the state updates to the frontend to update the UI.

To maintain performance as your state grows, internally Reflex keeps track of vars that were updated during the event handler (dirty vars). When the event handler is done processing, we find all the dirty vars and create a state update to send to the frontend.

In our case, the state update may look something like this:

We store the new state in our state manager, and then send the state update to the frontend. The frontend then updates the UI to reflect the new state. In our example, the new Github profile image is displayed.

I hope this provides a good overview of how Reflex works under the hood. We will have more posts coming out to share how we made Reflex scalable and performant through features such as state sharding and compiler optimizations.

As always you can follow us for more: